This is a translation of a Finnish-language essay by Anu Partanen that was published just before the 2020 U.S. presidential election. The essay originally appeared on the cover of the Sunday section of Finland's largest newspaper, Helsingin Sanomat, here.

Helsingin Sanomat, Sunday Pages

October 31, 2020

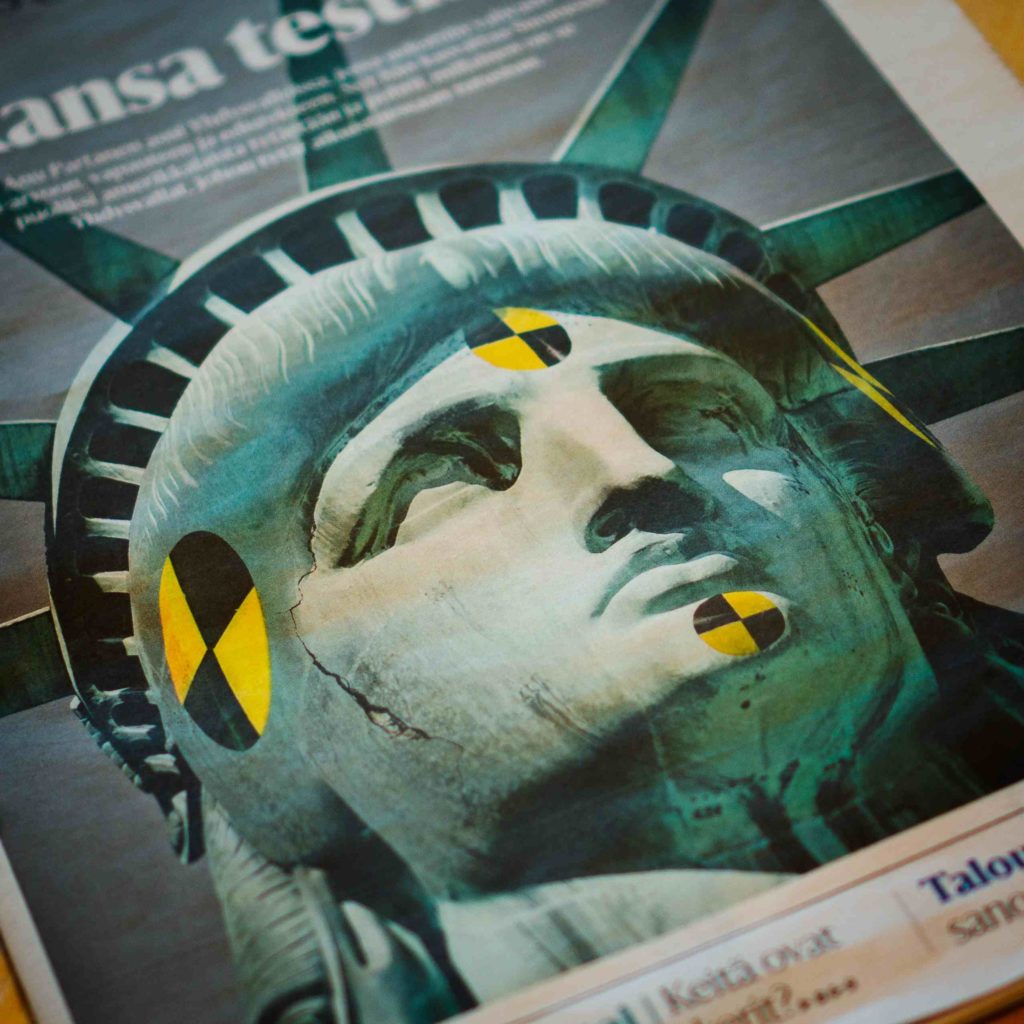

Crash-test Nation

Anu Partanen spent a decade in the United States, living among people who believe in equality, freedom, and progress. Now, as Partanen raises her half-American daughter in Finland, she wonders what kind of America her daughter will find waiting for her.

Photo of illustration by Klaus Welp for Helsingin Sanomat

by Anu Partanen

"I think we're headed for better times," our friend says. "We've reached the bottom now, and it's going to get better from here."

We stare at him.

"Really?" someone asks. The rest of us ask the same with our surprised silence, each in our own little square.

"Explain, please," says someone else.

This is what it's come to: a positive assessment of the future—if one can call positive an assessment that we are experiencing our darkest moment right now—sounds absurd to us, as if our friend had finally relinquished his grip on reality. Which, of course, wouldn't be all that odd these days.

The situation itself is also unusual because we are talking about the future of the United States. We're only talking about it because I asked my friends what they think about it.

We get together somewhat regularly on Saturdays. There are usually seven of us. For Californians the meeting is breakfast (Bloody Marys), for New Yorkers lunch (wine), and for us in Helsinki dinner (it's already time for something stronger, isn't it?).

We compare our meals. We talk about work, co-op meetings, TV shows, bike rides, pets, and families. We laugh.

Sometimes we discuss practical questions: Is it safer to travel between Manhattan and Brooklyn by subway or Uber when considering the risk for Covid? Is there an argument that could make a Trump-voting grandmother change her mind? Can a massage be had outdoors? (Of course, if you happen to live in California.)

Since many in our group of friends are teachers, we discuss the challenges of remote teaching. We discuss smoke days in California schools, when teachers and students are banned from campus because the air quality is too poor for outdoor activities—this is because of the forest fires, but many school activities can't take place indoors because of the pandemic.

Most of the time we don't discuss politics, even though we are all American citizens and entitled to vote. This does not surprise me. I myself feel too tired to discuss it all, even though my mail-in vote has left Helsinki for the U.S. weeks ago.

What is there to discuss when there's a car crash, and you're sitting inside the wreckage yourself?

What is there to tell in a story whose twists and turns have already been watched with disbelief, whose logic has long ago disappeared, and of which all that is left is a tangle with no beginning and no end?

• • •

I moved to the U.S. in late 2008. One of my first memories of life in the U.S. is watching Barack Obama's inauguration ceremony on an old TV set in Brooklyn.

The TV commentators kept repeating the phrase "peaceful transition of power." As in: "We have gathered here today to once again observe the peaceful transition of power." The emphasis sounded strange to me—what exactly did the narrators expect might happen on that stage? A fist fight between the outgoing and the incoming president?

During my first year in the U.S., I divided my time between California and New York. In San Francisco, my Indian-American roommate had attached a campaign poster featuring Obama's stylized face on the refrigerator. In Brooklyn, Obama's "Yes We Can" campaign signs were attached to the windows of homes.

I imagined myself in Helsinki attaching a picture of Finland's prime minister Matti Vanhanen or President Tarja Halonen on my fridge. The thought made me laugh. I could not remember a single Finnish political slogan.

As time passed, my confusion continued as I listened to the way Americans kept repeating the word freedom. We should be grateful that we live in a country where we have freedoms that others do not have, a rodeo host reminded us. Sometimes freedom is taken away by tanks; sometimes it is taken away when you and your family lose the freedom to choose your doctor, an opponent of Obama's health care reform said. In the U.S. the word "freedom" can be attached to just about any debate. To my Finnish ear, the use of the word of sounded pompous and self-aggrandizing.

Gradually, however, I began to grasp the story that Americans so tirelessly told themselves and others about their country.

Gradually, I also began to believe it.

• • •

The U.S. has historically been a safe haven for people freeing oppression. Thanksgiving still celebrates the Puritans who arrived on the new continent from Britain in the 17th century to escape religious persecution. When the U.S. declared independence in 1776, it also declared every human being to be born free and equal. The new country became a republic.

In reality, of course, the people living in the newly created U.S. were not equal by any measure. Slavery was legal and widespread in the country, and women were not allowed to vote.

Even so, in the world of that time, American thinking on equality was so radical that in the first half of the 19th century, the French diplomat Alexis de Tocqueville wrote his still-famous book Democracy in America about his experiences in the U.S. De Tocqueville admired the U.S.'s success with local government and representative democracy. Europe was still ruled by royals and nobles and had nothing like it.

In the late 19th century, millions of Europeans began flowing to Ellis Island in New York City. The Statue of Liberty rose next to the immigrant inspection station, and on its pedestal, Emma Lazarus' poem was carved: "Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…"

Later, the United States fought against the Nazis in Europe and continued to receive new waves of freedom seekers: German and Soviet Jews, Cuban conservatives, the poor and the crushed of South America and the Caribbean. The newcomers' stories varied, but almost everyone had experienced oppression of one kind or another: by dictators, by the masses, or by criminal groups.

I began to appreciate the almost obsessive attitude Americans had toward freedom. In their self-image, Americans are the pioneers of freedom and equality, because that is what they really have been in their own way for centuries.

Equality was also linked to the American perception of being American. According to the American self-image, the U.S. was different from Europe in another way: being American was not linked to shared genes or history. Being American was tied to the ideal of freedom. Anyone can be a true, patriotic American, as long as they are a U.S. citizen and believe in individual freedom and responsibility as well as in hard work and entrepreneurialism. Skin color, religion, and family history should not define who is American.

This mix of languages, cultures and religions has created the world's best universities, the biggest number of Nobel Prize-winning scientists, the most successful companies, the most revolutionary inventions, the most prosperous middle class, the most entertaining popular culture, and the world's only people to walk on the moon. It has created the most powerful and richest state in the world. Much of the rest of the world admires and follows.

The election of Barack Obama, the first African-American president of the United States, only seemed to reinforce this American story. Equality progresses slowly but surely. Obama's picture on the fridges was a tribute not only to his personality but also to the journey the U.S. had made.

Until: the sound a deafening scratch across the vinyl record interrupts the music.

• • •

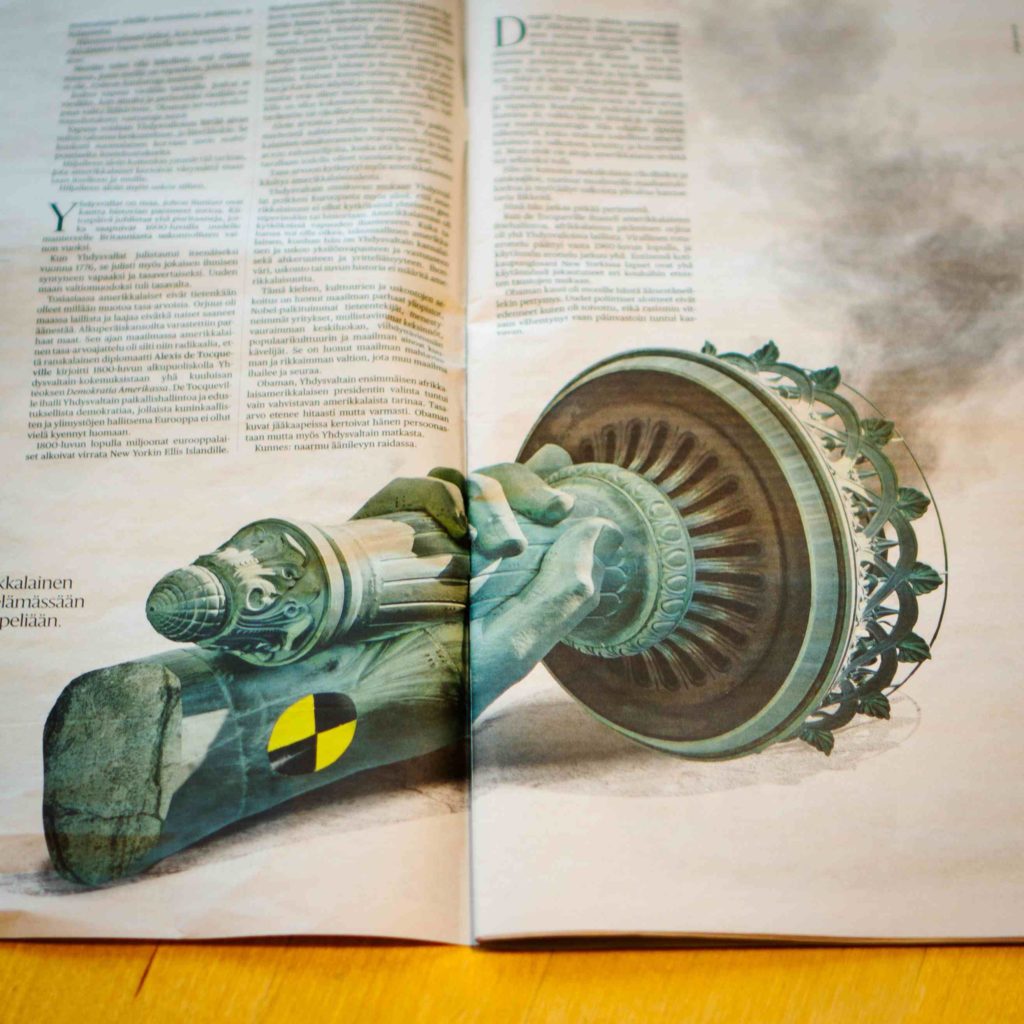

Photo of illustration by Klaus Welp for Helsingin Sanomat

Donald Trump's election as president came as a surprise mostly to liberal white Democratic voters who believed in the American story. Black Americans were perhaps less surprised—of course the rise of a black president would cause a backlash. Trump just made visible what had always simmered beneath the surface.

Trump does not care about the self-image of the U.S.—as a nation based on immigration, or united by the ideals of equality and freedom. No, not even though his mother and wife are immigrants. He proudly represents the view that a real American is white, Christian, and conservative. Others are not and cannot be truly American.

He has called Mexicans criminals and rapists, demanded a travel ban for Muslims and sided with white supremacist movements. In doing so, he follows a long tradition.

During the time when de Tocqueville admired American self-government, keeping Africans as slaves was still legal in the U.S. Official racial segregation did not end until the late 1960s, and unofficial segregation still continues. In my former hometown of New York City, children still end up divided into different schools according to ethnic backgrounds.

The Obama presidency was a disappointment to many who voted for him. New political initiatives did not proceed as hoped, and the scourge of racism did not diminish but, on the contrary, seemed to grow. Michael Brown; Ferguson, Missouri. Sandra Bland; Waller County, Texas. Tamir Rice; Cleveland, Ohio. Eric Garner; Staten Island, New York. Breonna Taylor; Louisville, Kentucky. George Floyd; Minneapolis, Minnesota ...

Names and videos came in a stream year after year. Black men, women and children dying at the hands of white police officers without anyone being punished.

The events were followed by local demonstrations, a wave of news, and an avalanche of social media. But it wasn't until the Trump era that Black Lives Matter, a movement denouncing the discrimination and the police violence that black Americans face daily, spread across the country and became known around the world. The American story of equality, freedom, and progress crumbled. The reality looked different.

• • •

What does American life look like? What about American health care? School? School lunch? Working conditions? Pay? Summer vacation? Parental leave? Sick leave? Taxation?

There are as many answers as there are Americans.

With their faith in individual freedom and responsibility, Americans forgot that equality of opportunity does not happen by itself and that a common reality arises only from a common framework. If everyone has to negotiate, fight, and pay for themselves and their families the kind of health insurance, childcare, education, family leave, employment, and taxation that their skills, money, and connections can achieve, no one has any idea what kinds of difficulties or opportunities others are facing.

It took a while before I began to understand that every American really is building their very own puzzle in life, and that they mostly don't have any idea what kinds of pieces other people's puzzles are made of.

The political decisions made in the U.S. over the past forty years are essentially a cautionary tale. The decisions have favored the wealthy and, under the guise of freedom, built a society in which an individual's family background and wealth determine their success much more than their entrepreneurialism or talent, and a society in which people live completely different lives. Inequality and mistrust reign.

Now, Americans have begun to talk more and more about two different political realities: the one that journalists write about and social media talks about, and the one that ordinary voters experience. These two worlds seem less and less likely to meet.

Reporters uncover one political scandal after another, and social media and cable TV commentators deliver opinions every day, but ordinary voters aren't persuaded, or even reached.

More and more Americans believe in lies and conspiracy theories because—why not? The history of the U.S. can also be seen as one big fairy tale and as a true conspiracy. The actions of American intelligence services and presidents have often constituted proven conspiracies, and perhaps the biggest lie of all has been the claim of equality of opportunity. It's not hard to plant more lies and arguments in such soil if you want to, and there are many in the world today who do.

Ordinary voters cite low hourly wages and deteriorating morale as their biggest concerns. But the political elites are talking about Russia or Ukraine. So, perhaps it's no wonder that, according to a study by Stony Brook University in the U.S., more than 80 percent of Americans follow politics only occasionally or not at all.

• • •

I moved back to Finland in 2018, a year and a half after Donald Trump's inauguration. Over the past two years, I have visited the U.S. only a few times on business trips. I meet my American friends and my partner's family on video calls, and I follow the lives of my American acquaintances on Instagram. The U.S. in the news and on public social media looks very different from the U.S. I see in my meetings or on private social media.

The news stream grinds Trump, Covid, Supreme Court judges, election campaigns, and the stock market. My acquaintances share pictures of nature, children learning to ride bikes, and ice cream servings at local restaurants.

Their pictures remind me of everything that I love in the U.S. Funny, smart, and caring people, rugged, breathtaking nature, neighborhood communities, and an energetic, enterprising, and highly social culture.

That U.S., too, is real and still there, even though the nature photos show traces of forest fires, and even though my friends sometimes seem to be collapsing in the midst of a year of homeschooling, remote work, and political catastrophe.

My Finnish acquaintances are obsessed with U.S. politics and the presidential election, some waking up at four in the morning to watch the debates. Among my American friends, no one wants to talk about politics. Some work as volunteers for one campaign or another in their own state. Many take part in demonstrations. Many report on social media that they voted or participated in get-out-the-vote campaigns by sending cards to people across the country. As far as I know, they all vote.

But everyone is also exhausted.

During the Democratic primaries, many of my friends and acquaintances took a strong stand for their own candidate. Now that choice is behind us, and two candidates have been fighting for power. Because of the American electoral system, though, most of the country has virtually no influence on the election of the president. The choice is made in the swing states. My friends, even the ones from those places, do not live there anymore.

On the other hand, all Americans have lived in a nation where the rise of chaos like the chaos we see now has long been possible. So, whose fault is this mess? Mine, yours, ours, theirs? Where is the beginning and where the end? Have previous votes for previous candidates actually altered anything? What about protests, scandals, and riots? Hillary Clinton got three million more votes than Donald Trump—yet Donald Trump won. Will anything ever change, and if so, who can bring about that change?

Obama supporters tried to revolutionize the system, but was anything transformed? Trump supporters tried the same from their own point of view—did they get a better reality?

In the end, only a tired silence follows the ongoing scandals of the political machinery, the street protests, and the noise of social media.

Fatigue, because managing day-to-day life is hard enough. Despair, because no action seems to have an impact. Silence, because you can't fight all the time, and rage takes its toll, too. But the silence can also speak of privilege—if the problems of the U.S. do not directly threaten you or your loved-one's livelihood or life, it's easier to leave the battle to others.

Sometimes I think that Finns follow American politics like passersby staring at a car wreck on the road. The destruction is exciting because it's shocking, without directly impacting you.

Americans, on the other hand, are in the accident. They pull frantically on the jammed car doors, or sit on the sidewalk in a state of shock. Some deny the events of the accident altogether. Others try to focus on their own affairs because the accident has already happened, and the damage is too difficult to fix.

When asked, they offer some opinion about traffic rules. But mostly they would rather talk about something else.

Everyone is more or less traumatized.

• • •

Photo of illustration by Klaus Welp for Helsingin Sanomat

I am often asked if I would still like to move back to the U.S. My answer has always been automatic: of course.

My partner is American. My daughter is half American. I am a dual citizen. I have taken it for granted that at some point our family will live in the U.S. again. After all, we want our daughter to know and experience the best of her other homeland.

She watches videos sent by her American uncle of the tractors cleaning the deserted beaches of California—the kid is obsessed with trucks and construction equipment—and she reads children's books about the lives of American children sent by her American grandparents. She lifts up her drawings for our American friends to admire via webcam.

For her, the U.S. is a place where people we love live and where we will go by plane one day. When everything is better.

One night when my husband and I are going to bed a whole new thought suddenly pops into my mind. What if everything is never better again?

My assumption that we will live in the U.S. again someday is based on the assumption that at some point the country will return to "normal." One day it will again be a country where my daughter can join a debate club at school, become friends with children who look very different from her, apply for and get jobs despite her strange Finnish name, and absorb a culture that believes in personal initiative, helping neighbors, and everyone's ability to change the world.

Fundamentally, I believe the United States is that same country even today.

But what if it isn't?

What if it is a country on a long-run trajectory towards fascism, terrorist attacks, climate catastrophe, and permanent chaos?

At times, I think I dramatize the situation in the U.S. too much. Sometimes, I think I don't dramatize it enough.

I hold on to a thought I encountered in a collection of essays by the British author Zadie Smith. Smith lives and teaches in the U.S. In these essays she reflects on the events of the pandemic spring. Our longing to return to the past is understandable but absurd, she says. After World War II, no one wanted to go back to the time before that. Disaster demanded a new dawn, Smith writes.

For the U.S., it is hard to believe in a new dawn. The slide into divergent realities has been so long, and views on future goals are so diverse. Four more years of Donald Trump would only bring more destruction, but four years of Joe Biden will hardly be enough to significantly improve the situation.

I can only think of the wider history of mankind. Empires rise and fall, wars and pandemics light up and go out. Stories are always just stories that need to be built into reality.

Maybe the United States will still rise and build its story into a new reality. Maybe my friend is right, and the bottom has already been reached.

I look at news photos of Americans queuing for hours at early voting sites in town halls, sports stadiums and youth centers. I'm moved. Although the whole country is in chaos, the electoral process is a mess, and the future is unknown, so many insist on having their voices heard.

A new dawn always comes in the end. Maybe it still looks beautiful.

Anu Partanen is the author of The Nordic Theory of Everything: In Search of a Better Life.